MERCED, Calif. — New farmland-mapping research published today shows that up to 90 percent of Americans could be fed entirely by food grown or raised within 100 miles of their homes.

Professor Elliott Campbell, with the University of California, Merced, School of Engineering, discusses the possibilities in a study entitled “The Large Potential of Local Croplands to Meet Food Demand in the United States." The research results are the cover story of the newest edition of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, the flagship journal for the Ecological Society of America, which boasts a membership of 10,000 scientists.

Professor Elliott Campbell, with the University of California, Merced, School of Engineering, discusses the possibilities in a study entitled “The Large Potential of Local Croplands to Meet Food Demand in the United States." The research results are the cover story of the newest edition of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, the flagship journal for the Ecological Society of America, which boasts a membership of 10,000 scientists.

“Elliott Campbell's research is making an important contribution to the national conversation on local food systems,” influential author and UC Berkeley Professor Michael Pollan said. “That conversation has been hobbled by too much wishful thinking and not enough hard data — exactly what Campbell is bringing to the table.”

The popularity of “farm to table” has skyrocketed in the past few years as people become more interested in supporting local farmers and getting fresher food from sources they know and trust. Even large chain restaurants are making efforts to source supplies locally, knowing more customers care where their food comes from.

“Farmers markets are popping up in new places, food hubs are ensuring regional distribution, and the 2014 U.S. Farm Bill supports local production — for good reason, too,” Campbell said. “There are profound social and environmental benefits to eating locally.”

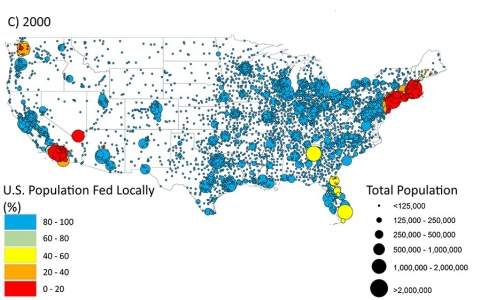

Local food potential has declined over time, which Campbell said was an expected finding, given limited land resources and growing populations and suburbanization.

The surprise, though, was how much potential still remains.

Most areas of the country could feed between 80 percent and 100 percent of their populations with food grown or raised within 50 miles. Campbell used data from a farmland-mapping project funded by the National Science Foundation and information about land productivity from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

With additional support from the University of California Global Food Initiative, he found there is enough land to assure that eating locally doesn’t have to be a passing fad.

“These results are very timely with respect to increasing interests by the public in community-supported agriculture, as well as improving efficiencies in the food-energy-water nexus,” said Bruce Hamilton, program director for NSF, which supports a spectrum of emerging technologies that might help alleviate growing agricultural demands.

Campbell and his students looked at the farms within a local radius of every American city, then estimated how many calories those farms could produce. By comparing the potential calorie production to the population of each city, the researchers found the percentage of the population that could be supported entirely by food grown locally.

The researchers found surprising potential in major coastal cities. For example, New York City could feed only 5 percent of its population within 50 miles but as much as 30 percent within 100 miles. The greater Los Angeles area could feed as much as 50 percent within 100 miles.

Diet can also make a difference. For example, local food around San Diego can support 35 percent of the people based on the average U.S. diet, but as much as 51 percent of the population if people switched to plant-based diets.

Campbell’s maps suggest careful planning and policies are needed to protect farmland from suburbanization and encourage local farming for the future.

“One important aspect of food sustainability is recycling nutrients, water and energy. For example, if we used compost from cities to fertilize our farms, we would be less reliant on fossil-fuel-based fertilizers,” Campbell said. “But cities must be close to farms so we can ship compost economically and environmentally. Our maps provide the foundation for discovering how recycling could work.”