You can smell them a mile away; there’s no mistaking the smell of cows and their methane emissions.

The odor, of course, comes from tons of methane-spewing manure. Thanks to a multimillion-dollar grant from the California Strategic Growth Council’s competitive Climate Change Research Program, Professor Gerardo Diaz and his interdisciplinary team of UC Merced faculty will look to subdue that stench while also caring for the planet.

The Climate Change Research Program is part of California Climate Investments, a statewide initiative that puts billions of cap-and-trade dollars to work reducing greenhouse gas emissions, strengthening the economy and improving public health and the environment — particularly in disadvantaged communities.

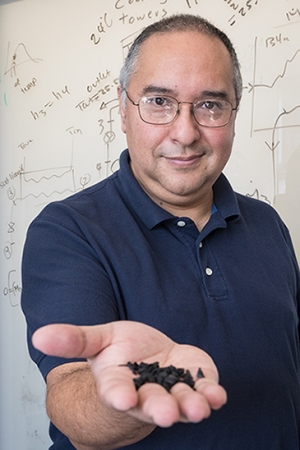

Diaz and professors YangQuan Chen and Catherine Keske from the School of Engineering and professors Asmeret Berhe, Teamrat Ghezzehei and Rebecca Ryals from the School of Natural Sciences will use the $3 million grant to examine how biochar can be produced and used to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, namely methane. The team will explore the feasibility of a mobile biochar unit through technology development and field testing.

Biochar is a byproduct of burning biomass such as dead trees and shrubs, or agricultural remains. Biochar’s properties depend on how it is produced — different temperatures and the inclusion of elements such as oxygen or steam can change how it would work for different soils and conditions.

“California is one of the few places in the world where use of biochar for management makes a lot of sense, in particular because we typically have a lot of excess biomass form agriculture or forestry operations,” said Berhe. “With the massive tree die-off in the Sierra Nevada, biochar production from that biomass will have multiple benefits — reducing the amount of fuel in the forest to prevent large forest fires from spreading in the dry season and, with appropriate placement, improve the chemical and physical conditions of soil.”

Research has shown the addition of biochar to manure composting reduces methane emissions between 27 percent and 32 percent. Dairy farms are the single largest contributors to California’s man-made methane production, making them the perfect places to explore how to lower the emissions.

If the mobile biochar production is successful, methane emissions from manure could drop by at least 2.74 MMT CO2 per year, or the equivalent of nearly 550,000 hot air balloons. Current options for farmers are to purchase permits for open burning — which Diaz said can be expensive for small farms — or illegally burning the manure at night. The communities surrounding dairies are often low-income and disadvantaged, which Diaz said makes the potential for the research findings even more beneficial.

“The communities that are usually right next to these dairy operations, they usually live with this odor that is coming from the operation,” Diaz said. “By reducing the emissions of methane, we are helping all the aspects of greenhouse-gases reduction, but this material also has the capacity of removing the odors as well. That would significantly impact disadvantaged communities in a good way.”

Diaz said communities in Merced and Madera counties are the target of the three-year project, with expansion across the Central Valley as the ultimate goal.

The project will create a mobile biochar production unit that is at Technology Ready Level (TRL) 7, meaning it’s nearly ready to enter the market. The team will work with agriculture and manufacturing industry partners and local farmers on production. Although there is a stationary biochar production unit available in Ballico, Diaz believes a mobile unit will allow for more widespread use of biochar.

“In the past, the idea has been to have these plants that are stationary and people bring the biomass to that place, but that is a lot of transportation and pollution,” Diaz said. “If you have a small farmer who cannot even pay for the permit for open burning, how is he going to have the money to actually take it somewhere else to be utilized?”

The team believes with the help of the mobile unit, producers of biochar will be able to either use the product for their own farms or sell it to others for profit.

Most of the team members have worked with biochar in one way or another before, including Keske. The resource economist has researched biochar in Colorado and, most recently, in Canada, where she is part of a team examining sustainable biomass and waste management in the semi-arctic and boreal ecosystems of Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador, Canada.

Keske will research the economic feasibility of mobile biochar production, a challenge she said could ultimately decide the fate of mass biochar production for particular agricultural areas, including methane emission reduction.

“I think our findings have the potential to have an immediate impact on biochar production and the system in applying and using biochar,” Keske said. “If we can show positive correlation that it’s beneficial and I can show it’s economically feasible, I think California and the Central Valley are very poised to implement our results. That’s what is really exciting.”

All six team members are with UC Merced, and are also excited that they lend an interdisciplinary nature to the project that can be hard to find at a single university.

“All of the team members are world class researchers, each with a different specialty,” said Ryals. “It is a privilege to be able to approach the same challenge with people who contribute different perspectives. I truly believe this will improve the way we think, the way we connect our different tools and the way we think about the results.

“Integrating our disciplinary expertise will ultimately make our work more complete and impactful.”